Osteogenesis Markers

Related Symbol Search List

Immunology Background

Background

Osteogenesis markers are specific molecules or substances that serve as indicators of bone formation or osteoblast activity in the body. These markers play a crucial role in assessing bone health, bone remodeling processes, and various bone-related conditions. The measurement of osteogenesis markers provides valuable information about the rate of bone formation and turnover, helping in the diagnosis and monitoring of bone diseases such as osteoporosis, osteomalacia, and bone metastases.

Role of Osteogenesis Markers

- Assessment of Bone Formation: Osteogenesis markers help evaluate the activity of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for bone formation. Increased levels of these markers typically indicate enhanced bone formation.

- Monitoring Bone Health: By measuring osteogenesis markers, healthcare providers can track changes in bone turnover, assess response to treatment, and identify abnormalities in bone metabolism.

- Diagnosis of Bone Disorders: Abnormal levels of osteogenesis markers can provide insights into various bone diseases, aiding in early detection and management.

Detection and Measurement of Osteogenesis Markers

- Blood Tests: Osteogenesis markers can be measured in blood samples. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and other immunoassays are commonly used to quantify the levels of specific markers such as osteocalcin, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BALP), and procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (PINP).

- Urine Tests: Some osteogenesis markers, like N-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (NTX) and C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX), are excreted in urine. Urine tests are used to measure these markers to assess bone resorption and turnover.

- Imaging Techniques: Imaging modalities like dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and quantitative computed tomography (QCT) can also provide indirect information about bone turnover and density, complementing the measurement of osteogenesis markers.

- Bone Biopsy: In research settings or specific clinical scenarios, bone biopsies may be performed to directly assess bone formation and turnover by analyzing markers in bone tissue.

Overall, the detection and measurement of osteogenesis markers through various laboratory tests play a critical role in understanding bone metabolism, diagnosing bone disorders, and monitoring the response to treatment in patients with conditions affecting bone health.

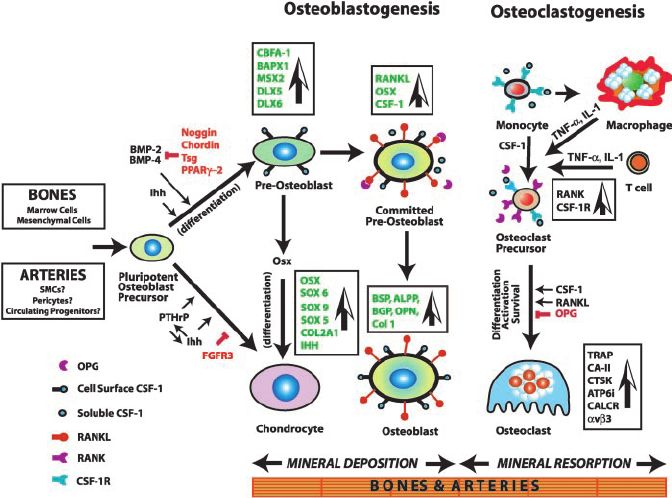

Fig.1 Mechanism of osteogenesis, showing the major genes, growth factors, and signaling pathways culminating in fully mature chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. (Doherty TM, et al., 2003)

Fig.1 Mechanism of osteogenesis, showing the major genes, growth factors, and signaling pathways culminating in fully mature chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. (Doherty TM, et al., 2003)Common Osteogenesis Markers

Common osteogenesis markers used to assess bone formation and osteoblast activity include:

- Bone-Specific Alkaline Phosphatase (BALP): An enzyme produced by osteoblasts during bone formation. Elevated BALP levels in the blood indicate increased bone formation.

- Runx2 (Runt-related transcription factor 2): Runx2 is a transcription factor critical for osteoblast differentiation and regulating the expression of other osteogenesis markers.

- Osteocalcin: Also known as Bone Gla Protein, osteocalcin is a protein produced by osteoblasts involved in bone mineralization. Levels in the blood reflect bone turnover.

- Procollagen Type I N-Terminal Propeptide (PINP): A marker of type I collagen synthesis and released during collagen formation by osteoblasts.

- Procollagen Type I C-Terminal Propeptide (PICP): Another marker of type I collagen synthesis, reflecting mature collagen formation in bone.

- Osteopontin (OPN): A protein secreted by osteoblasts that play a role in bone mineralization and remodeling.

- Bone-Specific Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain (COL1A1): A form of collagen type I, the predominant collagen in bone, used as a marker for bone formation.

- N-terminal Telopeptide of Type I Collagen (NTX): A marker of bone resorption, reflecting the breakdown of type I collagen in bone.

- C-terminal Telopeptide of Type I Collagen (CTX): Another marker of bone resorption, providing information on bone turnover.

Here are other osteogenesis markers:

| Classifications | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Bone Matrix Proteins and Collagens |

BGN (Biglycan): Biglycan is a small proteoglycan that interacts with collagen fibrils and contributes to the structural integrity of bone tissue. Col1a2 (Collagen Type I Alpha 2): Col1a2 encodes a subunit of type I collagen, the most abundant collagen in bone, providing tensile strength and flexibility to bone tissue. BGLAP (Osteocalcin): Osteocalcin is a non-collagenous protein produced by osteoblasts, playing a role in bone mineralization and a commonly used marker for bone formation. DMP1 (Dentin Matrix Protein 1): DMP1 is involved in the mineralization of bone and dentin, and mutations in this protein can lead to various bone disorders. |

| Regulatory Factors and Signaling Molecules |

IGFBP3 (Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3): IGFBP3 binds to insulin-like growth factors, regulating their activity in bone growth and metabolism. MEPE (Matrix Extracellular Phosphoglycoprotein): MEPE is involved in phosphate regulation and mineralization processes in bone. SCUBE3 (Signal Peptide, CUB, and EGF-Like Domain-Containing Protein 3): SCUBE3 may play a role in cell signaling pathways related to bone development and growth. SP7 (Osterix): SP7 is a transcription factor critical for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. |

| Extracellular Matrix Proteins | SPARC (Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine): SPARC is involved in bone mineralization, extracellular matrix formation, and tissue remodeling. |

| Other Factors |

TPO (Thyroid Peroxidase): While primarily associated with thyroid function, TPO mutations can impact bone health indirectly. ALPP (Alkaline Phosphatase, Placental Type): ALPP is a form of alkaline phosphatase associated with bone formation and is a marker for osteoblast activity. BCAP31 (B-cell Receptor-associated Protein 31): BCAP31 is involved in regulating osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. FGF23 (Fibroblast Growth Factor 23): FGF23 regulates phosphate and vitamin D metabolism, influencing bone mineralization. MCAM (Melanoma Cell Adhesion Molecule): MCAM may have roles in cell adhesion processes relevant to bone cell interactions. PDPN (Podoplanin): PDPN is a glycoprotein potentially involved in cell adhesion processes, which may relate to bone development. SOST (Sclerostin): SOST inhibits bone formation by antagonizing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and is a key regulator of bone remodeling. |

These markers collectively provide insights into various aspects of bone metabolism, development, and health, contributing to the understanding and management of bone-related disorders and conditions.

Changes and Interpretation of Osteogenesis Markers

Changes and Interpretation of Osteogenic Marker Levels

Changes in levels of osteogenesis markers can provide valuable insights into bone metabolism, turnover, and overall bone health. Here's how changes in these markers can be interpreted:

| Changes | Interpretations |

|---|---|

| Increased Levels of Osteogenesis Markers |

Bone Formation: Elevated levels of markers like BGLAP (Osteocalcin) and ALPP (Alkaline Phosphatase) may indicate increased bone formation by osteoblasts. Bone Turnover: Higher levels of markers such as PINP and procollagen type I C-terminal propeptide (PICP) could suggest increased bone turnover, which may occur in conditions like Paget's disease or during fracture healing. |

| Decreased Levels of Osteogenesis Markers |

Reduced Bone Formation: Decreased levels of osteogenesis markers associated with bone formation may indicate impaired osteoblast activity, as seen in osteoporosis or chronic kidney disease. Decreased Bone Turnover: Lower levels of bone turnover markers like NTX and CTX may suggest reduced bone resorption, potentially indicating a state of low bone remodeling, as seen in some metabolic bone diseases. |

| Interpretation of Changes |

Bone Health: Changes in osteogenesis markers can help assess overall bone health and identify abnormalities in bone metabolism. Disease Diagnosis: Monitoring these markers can aid in diagnosing bone disorders such as osteoporosis, osteomalacia, or Paget's disease. Treatment Efficacy: Changes in marker levels can indicate the response to treatments targeting bone health, such as medications for osteoporosis or interventions for bone metastases. |

| Contextual Interpretation |

Clinical Context: Interpretation should consider the patient's clinical history, symptoms, and other diagnostic findings to understand the significance of changes in marker levels. Serial Monitoring: Serial measurements of osteogenesis markers over time can help track changes in bone metabolism and assess the effectiveness of interventions. |

In summary, changes in levels of osteogenesis markers can provide valuable information about bone health, turnover, and response to treatment, helping in the diagnosis and management of various bone-related conditions.

How Are Levels of Osteogenic Markers Used in the Diagnosis of Osteoporosis and Bone Disease?

Levels of osteogenic markers play a crucial role in the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis and other bone diseases. Here's how these markers are used in the context of diagnosing these conditions:

| Diagnosis and management | Details |

|---|---|

| Assessment of Bone Turnover |

Increased Bone Resorption: Elevated levels of bone resorption markers like CTX and NTX are often seen in conditions of increased bone turnover, such as osteoporosis. Decreased Bone Formation: Lower levels of bone formation markers like BGLAP (Osteocalcin) and ALPP may suggest reduced osteoblast activity, as seen in osteoporosis. |

| Monitoring Response to Treatment |

Antiresorptive Therapies: Changes in bone turnover markers can indicate the effectiveness of antiresorptive medications used to treat osteoporosis, such as bisphosphonates or denosumab. Anabolic Therapies: Increasing levels of bone formation markers may be observed in response to anabolic treatments like teriparatide or romosozumab. |

| Risk Assessment |

Predicting Fracture Risk: Osteogenic markers can aid in assessing the risk of fractures by providing insights into bone quality and turnover, which are important factors in fracture prediction. Identification of Bone Disorders: Abnormal levels of osteogenic markers can help identify underlying bone disorders beyond osteoporosis, such as Paget's disease or osteogenesis imperfecta. |

| Comprehensive Diagnosis |

Combined Assessment: Osteogenic markers are often used in conjunction with bone mineral density (BMD) measurements and other clinical assessments to provide a comprehensive evaluation of bone health. Diagnostic Clues: Patterns of marker alterations, along with clinical presentation and imaging findings, can offer diagnostic clues for specific bone diseases. |

| Serial Monitoring |

Longitudinal Tracking: Serial measurements of osteogenic markers allow for the monitoring of changes in bone turnover and response to treatment over time. Treatment Adjustment: Monitoring marker levels can help in adjusting treatment strategies based on the individual's response and ongoing bone health status. |

| Healthcare Provider Guidance |

Clinical Interpretation: Healthcare providers interpret changes in osteogenic markers in the context of the patient's overall health, medications, and specific conditions to guide diagnosis and treatment decisions. Individualized Care: The use of osteogenic markers in diagnosis is part of a personalized approach to managing bone diseases, considering each patient's unique profile. |

In summary, levels of osteogenic markers serve as valuable tools in the diagnosis, risk assessment, and management of osteoporosis and bone diseases, providing insights into bone metabolism, turnover, and response to treatments.

Applications of Osteogenesis Markers in Each Disease

Osteogenesis markers play a crucial role in understanding and diagnosing various bone-related diseases by providing insights into bone metabolism, turnover, and overall bone health. Here are some examples of how osteogenesis markers are applied in the context of different diseases:

| Disease | Markers and Applications |

|---|---|

| Osteoporosis | Markers Used: Bone turnover markers like serum C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX) and serum N-terminal propeptide of type I collagen (P1NP).

Application: These markers help in assessing bone turnover rates and monitoring the response to osteoporosis treatments. |

| Osteogenesis Imperfecta |

Markers Used: Collagen type I markers like procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (PINP) and C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx). Application: These markers aid in diagnosing and monitoring the severity of this genetic disorder characterized by brittle bones. |

| Paget's Disease |

Markers Used: Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and urinary hydroxyproline. Application: These markers are helpful in diagnosing and monitoring the disease activity and response to treatment in patients with Paget's disease of bone. |

| Bone Metastases |

Markers Used: Serum calcium, serum alkaline phosphatase, and urinary N-telopeptide. Application: These markers assist in detecting bone metastases and monitoring the progression of cancer in bones originating from primary tumors elsewhere in the body. |

| Osteosarcoma |

Markers Used: Osteocalcin and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase. Application: These markers can aid in the diagnosis and monitoring of osteosarcoma, a primary malignant bone tumor. |

| Rickets |

Markers Used: Serum calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, and parathyroid hormone (PTH). Application: These markers help in diagnosing and monitoring the bone-softening disease, rickets, often caused by vitamin D deficiency. |

| Bone Fractures |

Markers Used: Serum levels of collagen type I markers and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase. Application: These markers can help assess bone healing and predict fracture risk in individuals recovering from bone fractures. |

| Osteoarthritis |

Markers Used: Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP). Application: These markers are used to evaluate cartilage degradation and monitor disease progression in osteoarthritis. |

By utilizing osteogenesis markers specific to each disease, healthcare professionals can better diagnose, monitor disease progression, and tailor treatment strategies to improve patient outcomes in various bone-related conditions.

Case Study

Case 1: Xuan Y, Li L, Ma M, Cao J, Zhang Z. Hierarchical intrafibrillarly mineralized collagen membrane promotes guided bone regeneration and regulates M2 macrophage polarization. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;9:781268.

Mineralized collagen emerges as a promising barrier membrane material for guided bone regeneration (GBR) owing to its biomimetic nanostructure. The interaction between materials and the host immune system plays a crucial role in determining the success of GBR procedures. Nonetheless, existing barrier membranes fall short in clinical settings due to their limited mechanical strength and osteoimmunomodulatory properties.

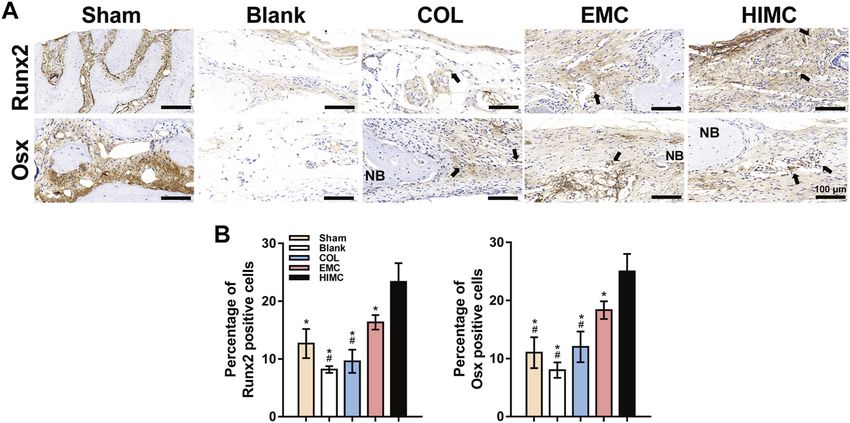

In a recent study, researchers developed a hierarchical intrafibrillarly mineralized collagen (HIMC) membrane and compared it with collagen (COL) and extrafibrillarly mineralized collagen (EMC) membranes. The HIMC membrane exhibited superior physicochemical characteristics by mimicking the nanostructure of natural bone. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) cultured on the HIMC membrane demonstrated enhanced proliferation, adhesion, and osteogenic differentiation capabilities.

Furthermore, the HIMC membrane facilitated the polarization of CD206+Arg-1+ M2 macrophages, leading to increased migration of BMSCs. In a rat model with skull defects, the HIMC membrane promoted the regeneration of new bone with greater bone mass and a more mature bone architecture. The expression levels of key osteogenic markers Runx2 and osterix, along with CD68 + CD206 + M2 macrophage polarization, were significantly upregulated.

Overall, the HIMC membrane creates a conducive osteoimmune microenvironment that enhances GBR outcomes, making it a promising material for future clinical applications in guided bone regeneration procedures.

Fig.1 Representative images of IHC staining for osteogenesis markers in the defect region of different groups.

Fig.1 Representative images of IHC staining for osteogenesis markers in the defect region of different groups.Case 2: Fielding GA, Sarkar N, Vahabzadeh S, Bose S. Regulation of osteogenic markers at late stage of osteoblast differentiation in silicon and zinc doped porous TCP. J Funct Biomater. 2019;10(4):48.

In recent years, synthetic bone graft applications have evolved, with a growing focus on enhancing the osteoinductive properties of calcium phosphates (CaPs) by incorporating metal trace elements. This study aims to explore the impact of silicon (Si) and zinc (Zn) additives in highly porous tricalcium phosphate (TCP) scaffolds on the markers of late-stage osteoblast cell differentiation.

By utilizing an oil emulsion method, researchers fabricated porous SiO2-doped β-TCP (Si-TCP) and ZnO-doped β-TCP (Zn-TCP) scaffolds with 0.5 wt.% SiO2 and 0.25 wt.% ZnO, respectively. The study employed reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to analyze the mRNA expression of key markers like osteoprotegerin (OPG), receptor activator of nuclear kappa beta ligand (RANKL), bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), and runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) on days 21 and 28 of osteoblast differentiation.

The findings revealed that the addition of Si and Zn inhibited the β to α-TCP phase transformation, improved density, and did not affect dissolution properties. Both Si-TCP and Zn-TCP scaffolds exhibited normal BMP-2 and Runx2 transcriptions initially. Furthermore, at day 21, the presence of Si and Zn positively influenced the osteoprotegerin: receptor activator of nuclear factor k-β ligand (OPG:RANKL) ratio in the scaffolds.

Overall, the study underscores how doped porous β-TCP scaffolds with Si and Zn can enhance the expression of osteoblast marker genes, such as OPG, RANKL, BMP-2, and Runx2, showcasing the pivotal role of trace elements in effectively regulating late-stage osteoblast cell differentiation markers.

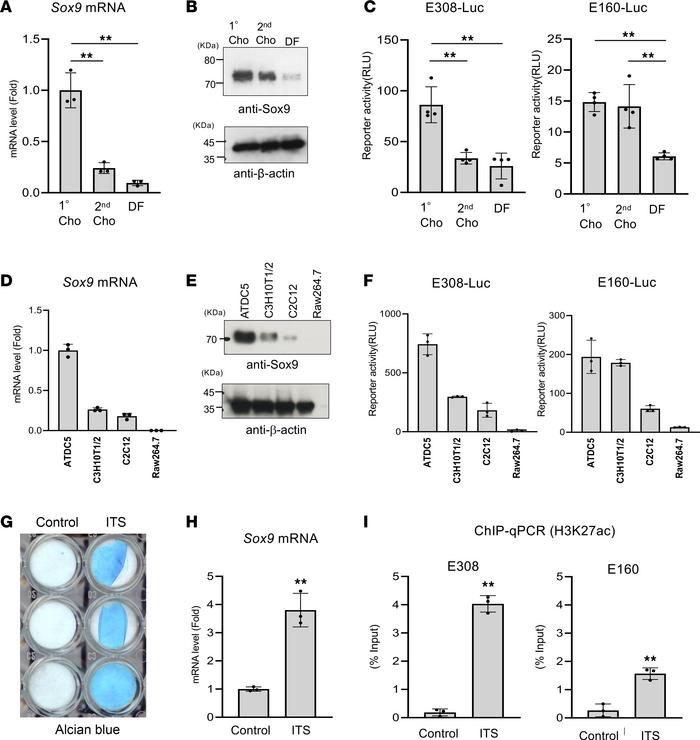

Fig.2 mRNA expression for BMP2, OPG, RANKL, and RUNX2 analyzed by RT-qPCR.

Fig.2 mRNA expression for BMP2, OPG, RANKL, and RUNX2 analyzed by RT-qPCR.Case 3: Shanbhag S, Suliman S, Bolstad AI, Stavropoulos A, Mustafa K. Xeno-Free spheroids of human gingiva-derived progenitor cells for bone tissue engineering. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:968.

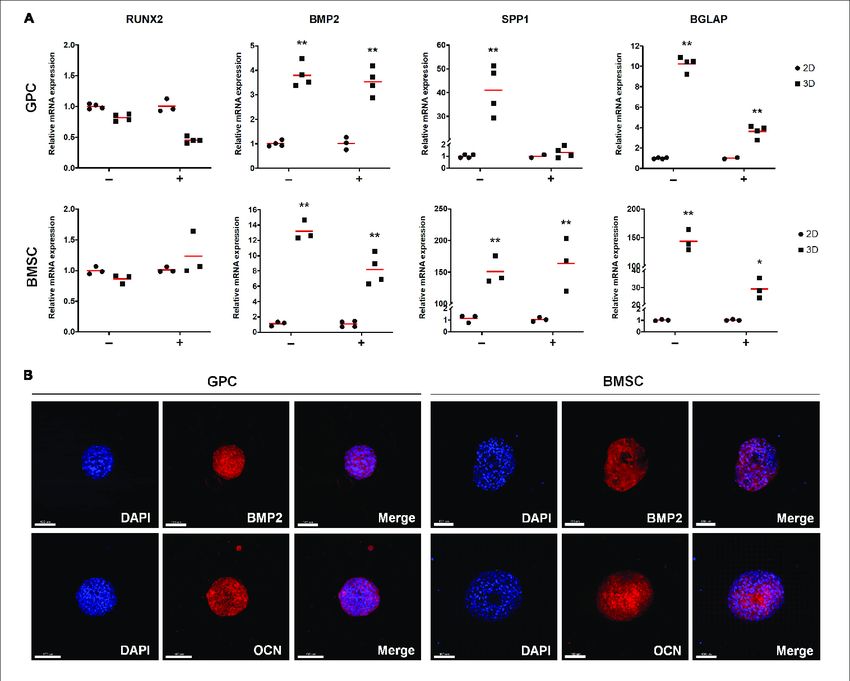

Gingiva serves as a minimally invasive source of multipotent progenitor cells (GPCs) crucial for bone tissue engineering (BTE). This study focused on characterizing human GPCs in xeno-free 2D cultures and exploring their osteogenic potential in 3D settings, comparing them with bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs). The research highlighted that monolayer GPCs in human platelet lysate (HPL) exhibit robust osteogenic differentiation akin to BMSCs. Notably, 3D spheroid cultures of GPCs and BMSCs in HPL demonstrate heightened expression of stemness- (SOX2, OCT4, NANOG) and osteogenesis-related markers (BMP2, RUNX2, OPN, OCN), along with increased secretion of growth factors and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines, aligning closely with BMSC behavior.

Fig.3 Expression of osteogenesis markers in xeno-free 3D spheroids.

Fig.3 Expression of osteogenesis markers in xeno-free 3D spheroids.Related References

- Doherty TM, Asotra K, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Calcification in atherosclerosis: bone biology and chronic inflammation at the arterial crossroads. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11201-11206.

- Amarasekara DS, Kim S, Rho J. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by cytokine networks. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(6):2851.

- Sato A, Kajiya H, Mori N, et al. Salmon DNA accelerates bone regeneration by inducing osteoblast migration. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169522.