Gametes and Fertilization

Creative BioMart Gametes and Fertilization Product List

Immunology Background

Background

Gametes and fertilization are fundamental processes in the biology of sexual reproduction that allow species to continue through generations. The formation of gametes, known as gametogenesis, and the subsequent fusion of these gametes during fertilization are key stages in the creation of a new organism. Understanding the structure, function, and interplay of gametes is critical for insights into developmental biology, genetics, and evolutionary theory.

Gametes

Definition and Types

Gametes are specialized reproductive cells produced by meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the number of chromosomes by half. In sexually reproducing organisms, two types of gametes are formed: sperm in males and eggs (ova) in females. These haploid cells contain half the number of chromosomes found in somatic cells, and their union during fertilization restores the diploid number of chromosomes.

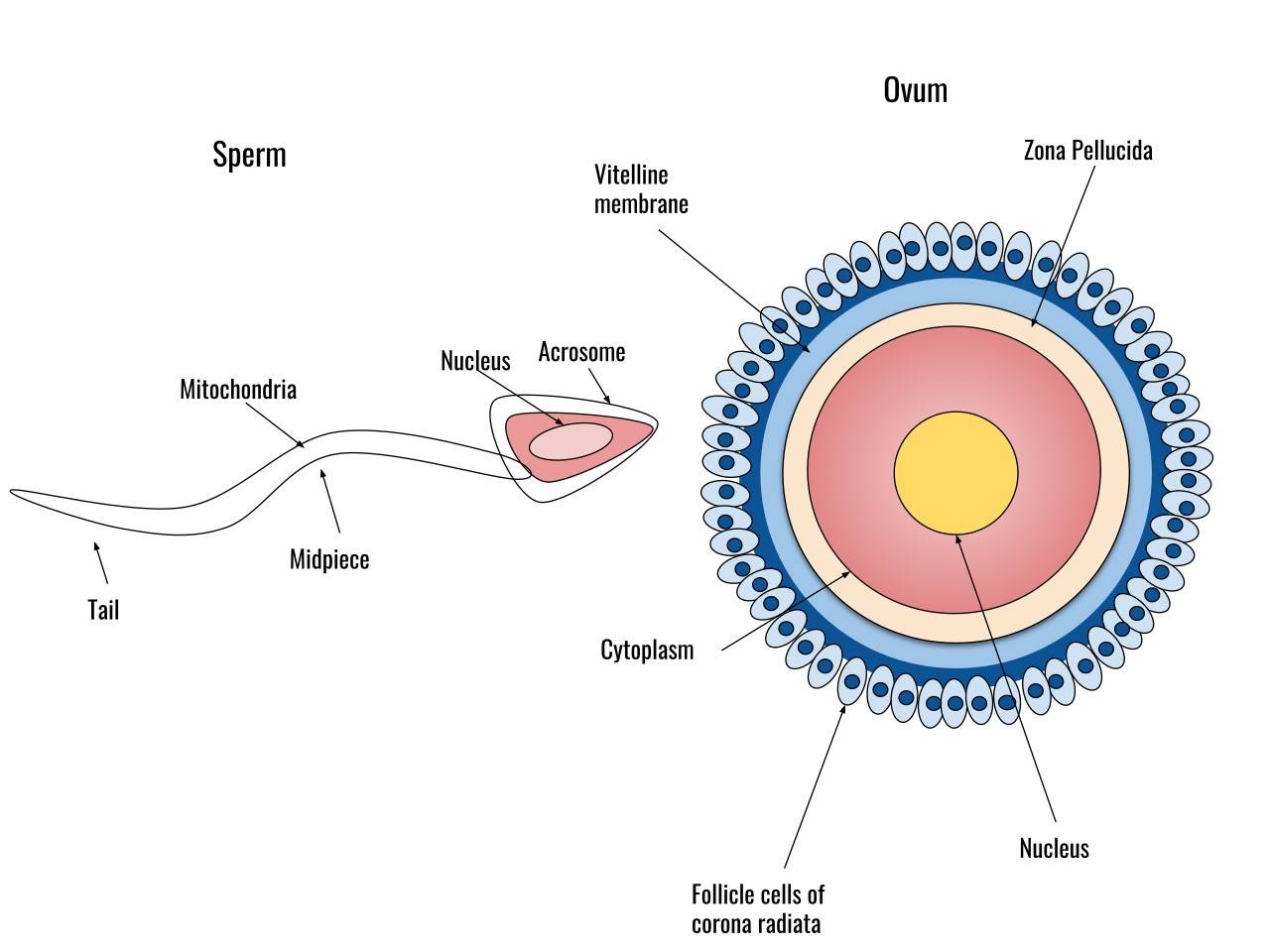

Sperm are typically small and motile, adapted to travel through the female reproductive tract to reach the egg. They are produced in the testes of males and have a head, which contains the genetic material (DNA), and a tail, which aids in movement. The head of the sperm contains an acrosome, a cap-like structure that plays a crucial role in fertilization by releasing enzymes that help the sperm penetrate the outer layers of the egg.

In contrast, eggs are larger, non-motile cells produced in the ovaries of female organisms. They contain not only genetic material, but also cytoplasmic components that will support the early development of the embryo. The egg is surrounded by protective layers, such as the zona pellucida in mammals, that help regulate interactions with sperm during fertilization.

Fig. 1: Diagram of a human sperm cell (left) and a human egg cell (right).

Fig. 1: Diagram of a human sperm cell (left) and a human egg cell (right).Gametogenesis: The Formation of Gametes

The formation of gametes occurs through the process of gametogenesis, which differs between males and females.

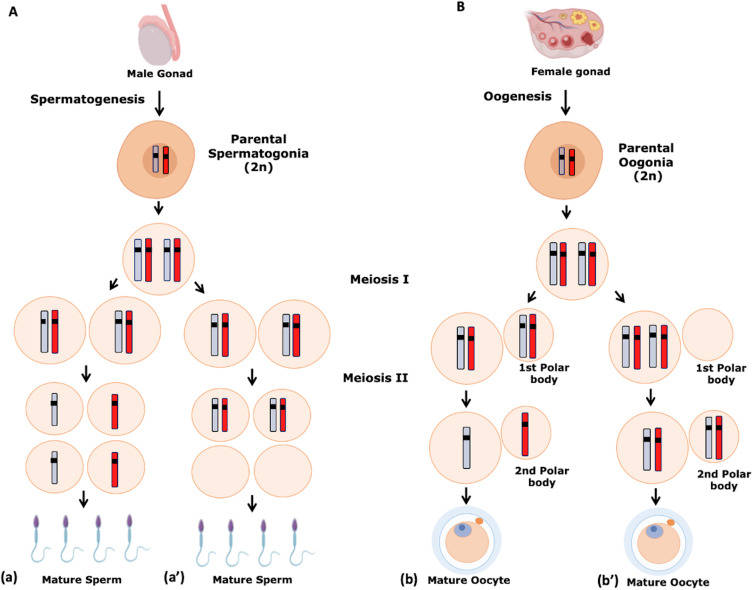

- Spermatogenesis: This is the process of sperm formation that occurs in the testes. Spermatogenesis begins with spermatogonia, diploid stem cells that undergo mitosis to produce primary spermatocytes. These primary spermatocytes undergo meiosis I to produce two secondary spermatocytes, which then undergo meiosis II to produce four haploid spermatids. These spermatids undergo a maturation process called spermiogenesis, which transforms them into fully functional spermatozoa. This continuous process begins at puberty and continues throughout the male's life.

- Oogenesis: Oogenesis, or egg formation, occurs in the ovaries. Unlike spermatogenesis, oogenesis begins during fetal development. Primordial germ cells differentiate into oogonia, which enter meiosis I and become primary oocytes. These primary oocytes are arrested in prophase I until puberty. At each menstrual cycle, one primary oocyte completes meiosis I to form a secondary oocyte and a polar body. The secondary oocyte begins meiosis II but is arrested in metaphase II and will only complete the division if fertilization occurs. Oogenesis is a cyclic and finite process, with a limited number of oocytes available throughout a female's reproductive life.

Fig. 2: Gametogenesis. Numerical chromosome disorders include duplication or loss of entire chromosomes, as well as changes in the number of complete sets of chromosomes. They are caused by nondisjunction, which occurs when pairs of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids fail to separate during meiosis. (A) Spermatogenesis. a. Normal spermatogenesis. a′. Aneuploidy in spermatogenesis. (B) Oogenesis. b. Normal oogenesis. b′. Aneuploidy in oogenesis (Martinhago and Furtado, 2022).

Fig. 2: Gametogenesis. Numerical chromosome disorders include duplication or loss of entire chromosomes, as well as changes in the number of complete sets of chromosomes. They are caused by nondisjunction, which occurs when pairs of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids fail to separate during meiosis. (A) Spermatogenesis. a. Normal spermatogenesis. a′. Aneuploidy in spermatogenesis. (B) Oogenesis. b. Normal oogenesis. b′. Aneuploidy in oogenesis (Martinhago and Furtado, 2022).Fertilization: The Union of Gametes

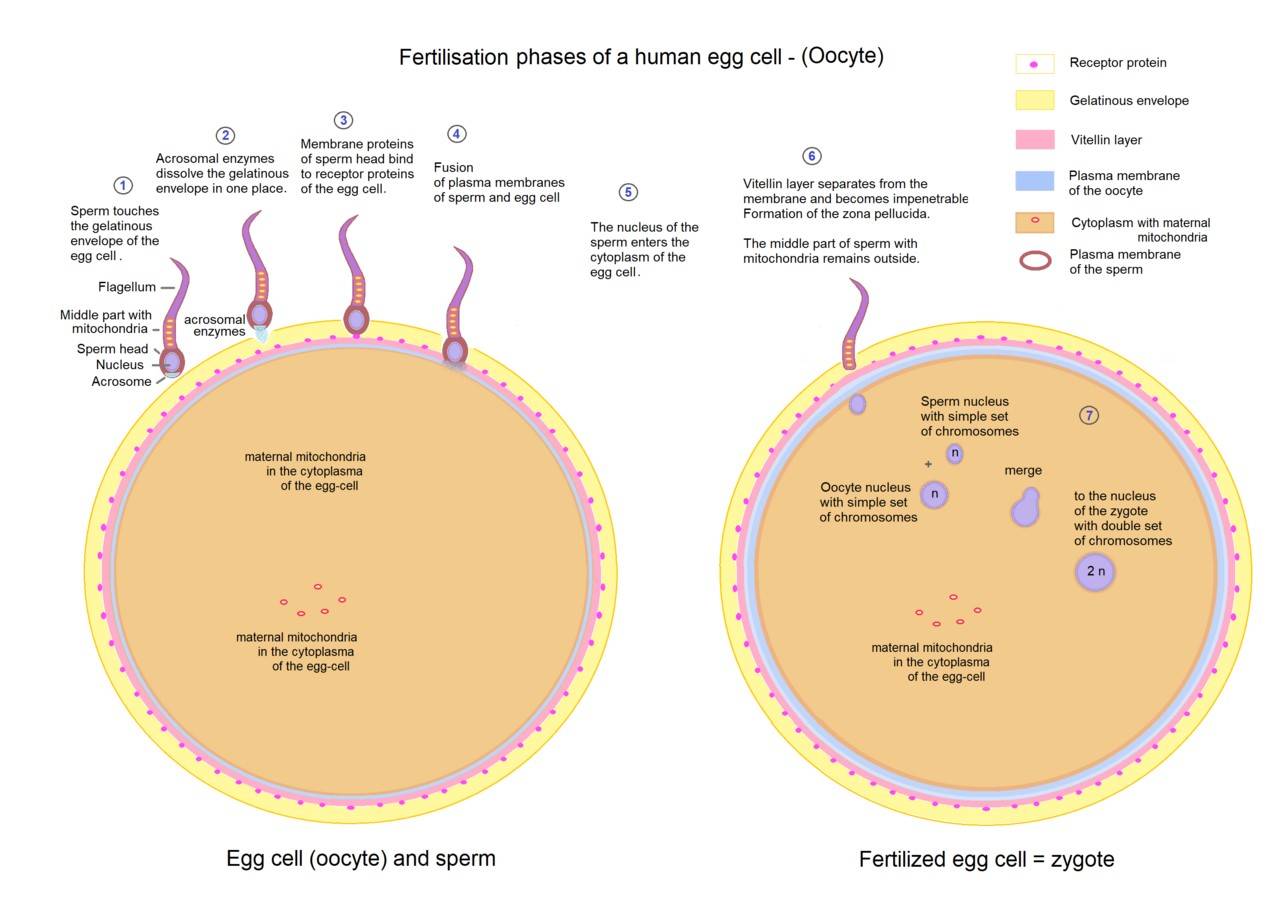

Fertilization is the process by which male and female gametes combine to form a zygote, marking the beginning of the development of a new organism. This complex process can be divided into several stages, each of which involves specific interactions between the sperm and the egg.

- Sperm-Egg Recognition: The first step in fertilization involves recognition between the sperm and the egg. In mammals, sperm must travel through the female reproductive tract to reach the egg, aided by chemotactic signals released by the egg. Once the sperm reach the vicinity of the egg, they must penetrate several protective layers, including the cumulus oophorus and the zona pellucida.

- Acrosome Reaction: When the sperm reaches the zona pellucida, it undergoes the acrosome reaction, a critical step where the acrosomal membrane fuses with the sperm's plasma membrane, releasing hydrolytic enzymes. These enzymes digest the glycoproteins of the zona pellucida, creating a path for the sperm to reach the egg's plasma membrane.

- Fusion of Sperm and Egg Membranes: Once the sperm has crossed the zona pellucida, it makes contact with the plasma membrane of the egg, resulting in membrane fusion. This fusion trigger the cortical reaction in the egg, a process that releases enzymes from cortical granules to modify the zona pellucida and prevent polyspermy, ensuring that only one sperm fertilizes the egg.

- Completion of Meiosis II: Upon sperm entry, the secondary oocyte completes meiosis II, producing the final oocyte nucleus and a second polar body. The sperm nucleus, now inside the egg cytoplasm, decondenses to form the male pronucleus.

- Pronuclear Fusion and Zygote Formation: The male and female pronuclei move toward each other and fuse, resulting in the formation of a diploid zygote with a complete set of chromosomes. This zygote will undergo a series of cell divisions called cleavage, leading to the development of a multicellular embryo.

Fig. 3: Overview of fertilization phases of a human egg cell.

Fig. 3: Overview of fertilization phases of a human egg cell.Molecular Mechanisms of Fertilization

Fertilization is not merely a mechanical event but is controlled by a series of molecular interactions. Sperm-egg binding is mediated by specific receptors on the surface of both gametes. In mammals, the zona pellucida protein ZP3 acts as a primary binding site for sperm. After the sperm binds to ZP3, the acrosome reaction is triggered, releasing enzymes that facilitate the penetration of the egg's extracellular matrix.

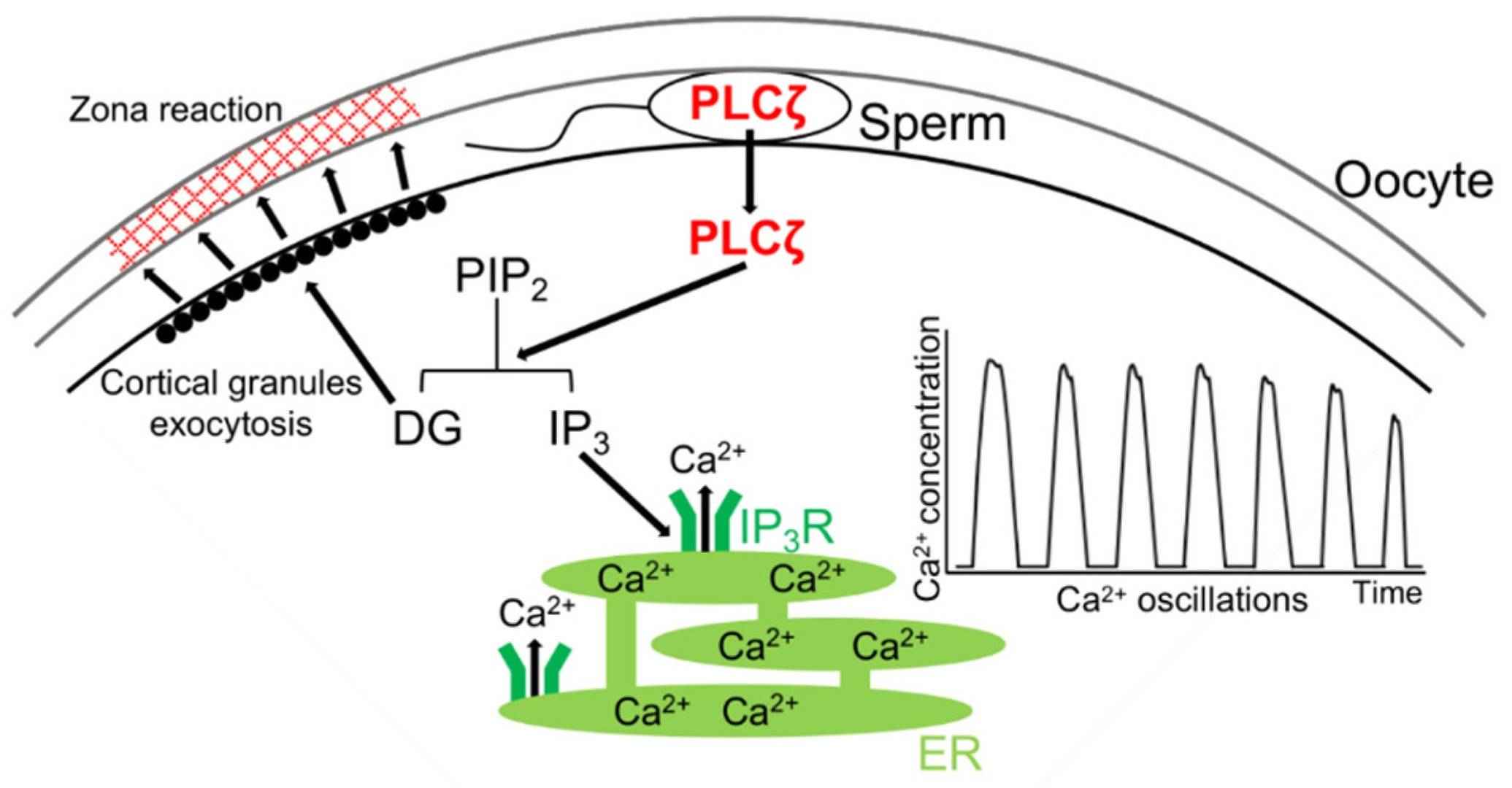

The cortical reaction, which prevents polyspermy, is another molecularly driven process. Once the sperm fuses with the egg membrane, an influx of calcium ions triggers the exocytosis of cortical granules. The contents of these granules modify the zona pellucida to make it impenetrable to additional sperm.

Signal transduction pathways also play an essential role in fertilization. The binding of sperm to the egg membrane activates downstream signaling pathways that ensure the successful completion of meiosis II and the initiation of zygotic development. Protein kinases, phosphatases, and other signaling molecules are involved in orchestrating the early events of fertilization.

Differences in Fertilization Among Species

Although the basic principles of fertilization are conserved among sexually reproducing organisms, there is considerable variation in the mechanisms of fertilization among species.

In external fertilization, which occurs in many aquatic species such as fish and amphibians, gametes are released into the environment and fertilization occurs outside the body of the organism. This method often involves the release of large numbers of gametes to increase the chances of successful fertilization.

In internal fertilization, as seen in mammals and reptiles, fertilization occurs within the female reproductive tract. This mode of reproduction provides greater protection for the gametes and the developing zygote, but generally results in fewer gametes being produced.

Fertilization and Early Development

After fertilization, the zygote undergoes a series of rapid cell divisions, a process known as cleavage. These divisions result in the formation of a blastocyst, which will eventually implant in the uterine wall in mammals or continue development in an oviparous species. Fertilization not only restores the diploid chromosome number, but also activates the oocyte and initiates the embryonic development process.

In some species, fertilization also determines sex. In humans, for example, the sperm contributes either an X or a Y chromosome, determining whether the offspring will be female (XX) or male (XY).

Key Molecules and Markers

Fertilization is a highly regulated process involving the interaction of several molecules and markers present on the surface of both gametes. These molecules and markers ensure proper recognition, binding, fusion, and activation during the union of sperm and egg. Below are some of the key fertilization molecules and gamete markers that play crucial roles in these processes.

Sperm Fertilization Molecules and Markers

- ZP3 Receptor: The zona pellucida protein 3 (ZP3) receptor is located on the sperm plasma membrane. It plays a central role in the initial recognition and binding of sperm to the zona pellucida (ZP), a glycoprotein layer surrounding the egg. The ZP3 receptor initiates the acrosome reaction, a critical step that allows sperm to penetrate the outer protective layers of the egg.

- Izumo1: Izumo1 is a protein found on the surface of sperm that is essential for sperm-egg fusion. It interacts with the egg's receptor Juno. Izumo1 is indispensable for sperm-egg membrane fusion. Male mice lacking this protein are infertile, indicating its critical role.

- ADAM Proteins (A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase): ADAM proteins, such as ADAM1 (ADAM1a, ADAM1b), ADAM2, and ADAM3, are involved in sperm-egg adhesion and binding to the zona pellucida. These proteins are necessary for sperm migration through the female reproductive tract and contribute to successful sperm-egg binding and fusion.

- Acrosomal Enzymes (e.g., Acrosin, Hyaluronidase): These enzymes are stored in the acrosome, a cap-like structure that covers the sperm head. Upon acrosome reaction, these enzymes are released and facilitate penetration of the zona pellucida. Acrosin and hyaluronidase break down the glycoprotein matrix of the zona pellucida, allowing the sperm to reach the plasma membrane of the oocyte.

- CatSper Channels: CatSper (Cation channels of sperm) are calcium ion channels located on the sperm tail. They regulate calcium ion influx, which is critical for sperm motility and hyperactivation. These channels play an important role in giving the sperm the ability to swim more powerfully towards the egg, especially during the final stages of fertilization.

Egg Fertilization Molecules and Markers

- ZP Proteins: Zona pellucida glycoproteins (ZP1, ZP2, ZP3, and ZP4) form the extracellular matrix surrounding the oocyte. ZP3 specifically mediates sperm binding and induces the acrosome reaction, while ZP2 is involved in sperm adhesion after the acrosome reaction. These glycoproteins regulate sperm recognition, ensuring that only sperm from the same species can bind to and fertilize the egg.

- Juno: Juno is the egg membrane receptor that binds to the sperm protein Izumo1 during the fusion process. The Juno-Izumo1 interaction is vital for sperm-egg membrane fusion. Following fertilization, Juno is rapidly lost from the oocyte membrane, preventing polyspermy (fertilization by more than one sperm).

- CD9: CD9 is a tetraspanin protein located on the egg membrane. It is involved in the fusion of the sperm and egg membranes. CD9 is critical for successful membrane fusion during fertilization. Mice lacking CD9 are infertile because sperm-egg fusion cannot occur.

- Cortical Granules: Cortical granules are secretory vesicles located just beneath the egg's plasma membrane. Upon sperm entry, they release their contents into the perivitelline space, leading to the modification of the zona pellucida. The release of cortical granule enzymes causes the zona pellucida to harden, a process known as the cortical reaction, which prevents additional sperm from fertilizing the egg (blocks polyspermy).

Signaling Molecules in Fertilization

- Calcium Ions (Ca²⁺): Calcium ions play a critical signaling role in fertilization. Sperm entry triggers a wave of calcium release within the egg, known as the calcium oscillation or calcium wave. This calcium signaling cascade activates the egg, restarting meiosis and initiating embryonic development. Calcium waves are also involved in triggering the cortical response to prevent polyspermy.

- PLCζ (Phospholipase C Zeta): PLCζ is a sperm-derived enzyme that initiates the calcium oscillations in the egg after sperm entry. PLCζ catalyzes the production of inositol trisphosphate (IP3), which binds to receptors on the egg's endoplasmic reticulum, releasing stored calcium and triggering egg activation.

Fig. 4: Mechanism of rise(s) in intracellular Ca2+ level via PLCζ during mammalian fertilization. After the sperm–oocyte fusion, PLCζ is released from the sperm into the oocyte. PLCζ hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DG). DG induces the exocytosis of cortical granules, results in the zona reaction, and IP3 binds to the IP3 receptor (IP3R), which leads to the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Sugita et al., 2024).

Fig. 4: Mechanism of rise(s) in intracellular Ca2+ level via PLCζ during mammalian fertilization. After the sperm–oocyte fusion, PLCζ is released from the sperm into the oocyte. PLCζ hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DG). DG induces the exocytosis of cortical granules, results in the zona reaction, and IP3 binds to the IP3 receptor (IP3R), which leads to the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Sugita et al., 2024).- MAP Kinase Pathways: Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways are involved in the signaling cascade that regulates oocyte maturation and fertilization. MAP kinases are activated during egg activation following sperm entry, ensuring that the egg completes meiosis and that early embryonic development proceeds correctly.

- cAMP (Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate): cAMP is a secondary messenger molecule involved in the regulation of sperm motility and capacitation (the process by which sperm become capable of fertilizing the egg). Elevated levels of cAMP in sperm trigger changes in motility, such as hyperactivation, and enhance sperm's ability to penetrate the egg's protective layers.

Polyspermy Prevention Molecules

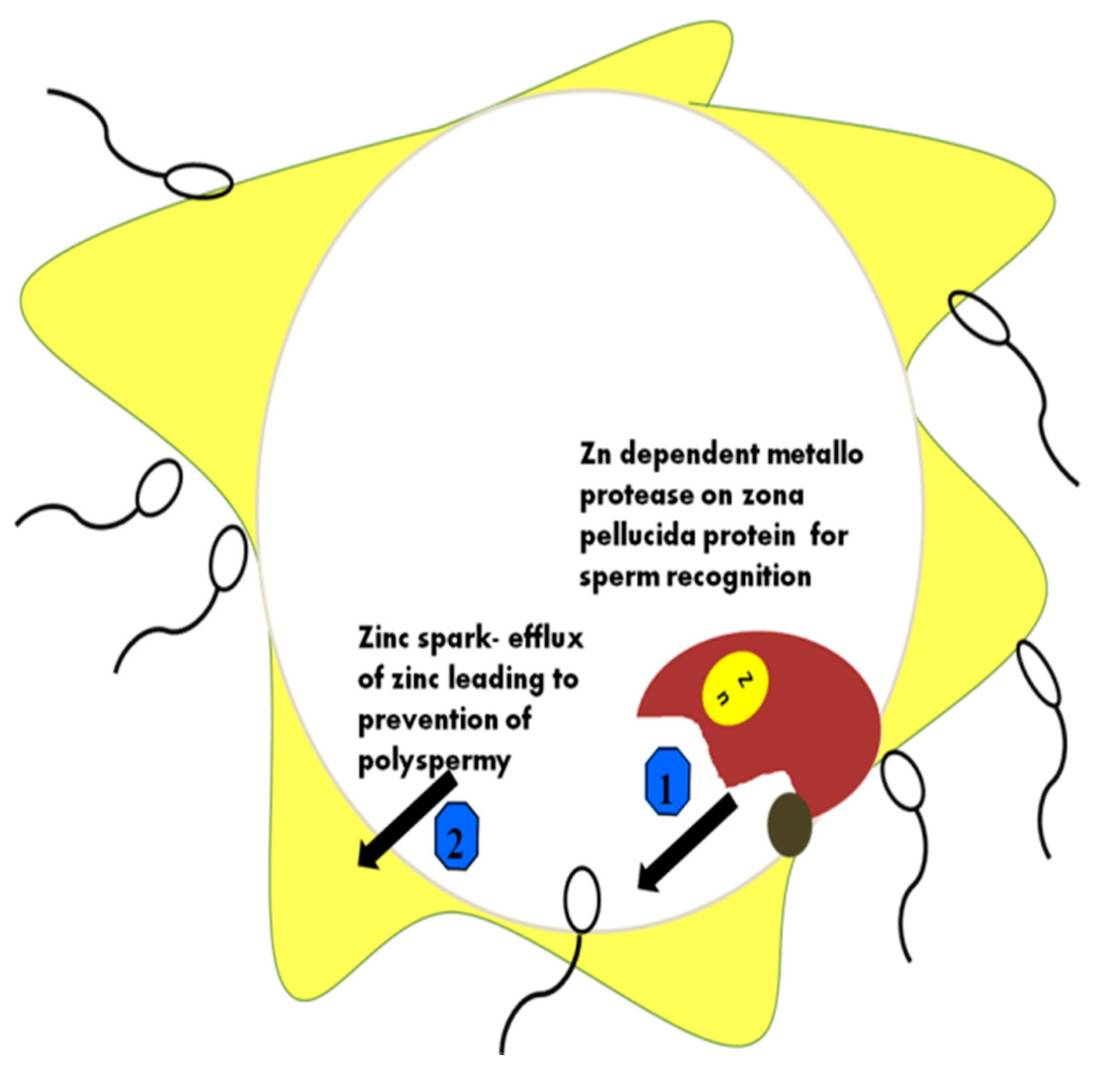

- Ovastacin: Ovastacin is a protease released from cortical granules following fertilization. It cleaves ZP2, which is critical for sperm binding. The cleavage of ZP2 by ovastacin prevents further sperm from binding to the zona pellucida, ensuring that only one sperm fertilizes the egg.

- Zinc Sparks: Zinc ions are released in bursts, known as "zinc sparks," from the egg after fertilization. Zinc sparks contribute to the block to polyspermy by modifying the zona pellucida and inhibiting the binding of additional sperm to the egg.

Fig. 5: Different roles of Zn ions during sperm–ova interactions. Zona pellucida (ZP) hardening occurs through membrane protein changes when the ZP protein acts using the Zn-binding protease. The major functions of zinc in the prevention of polyspermy are depicted in the figure. 1: Zn dependent metalloprotease on zona pellucida for sperm recognition; 2: how Zn efflux results in polyspermy (Vickram et al., 2021).

Fig. 5: Different roles of Zn ions during sperm–ova interactions. Zona pellucida (ZP) hardening occurs through membrane protein changes when the ZP protein acts using the Zn-binding protease. The major functions of zinc in the prevention of polyspermy are depicted in the figure. 1: Zn dependent metalloprotease on zona pellucida for sperm recognition; 2: how Zn efflux results in polyspermy (Vickram et al., 2021).In summary, the fertilization process is governed by a complex interplay of molecules and markers that regulate sperm and egg recognition, binding, fusion, and prevention of polyspermy. Key proteins such as Izumo1, Juno, CD9, and ZP glycoproteins provide species-specific interactions, while enzymes such as acrosin and molecules such as calcium ions drive the molecular cascades required for successful fertilization. Understanding these molecules provides critical insights into reproductive biology and has applications in fertility treatment, contraception, and reproductive technology.

Case Study

Case 1: Zheng, Y.; et al. Lack of sharing of Spam1 (Ph-20) among mouse spermatids and transmission ratio distortion. Biology of Reproduction. 2001, 64(6), 1730–1738.

Despite haploid gene action during mammalian spermiogenesis, gametic equality is presumed due to product sharing across intercellular bridges between spermatids. However, mice with different t-alleles, i.e. the mouse T (Brachyury) locus, which has been implicated in mesoderm formation and notochord differentiation, produce functionally different sperm, leading to transmission ratio distortion (TRD), the mechanism of which is unclear. Reduced levels of Spam1 mRNA, which is associated with TRD and reduced fertility in mice with Robertsonian translocations, correlate with decreased levels of its membrane protein and associated hyaluronidase activity.

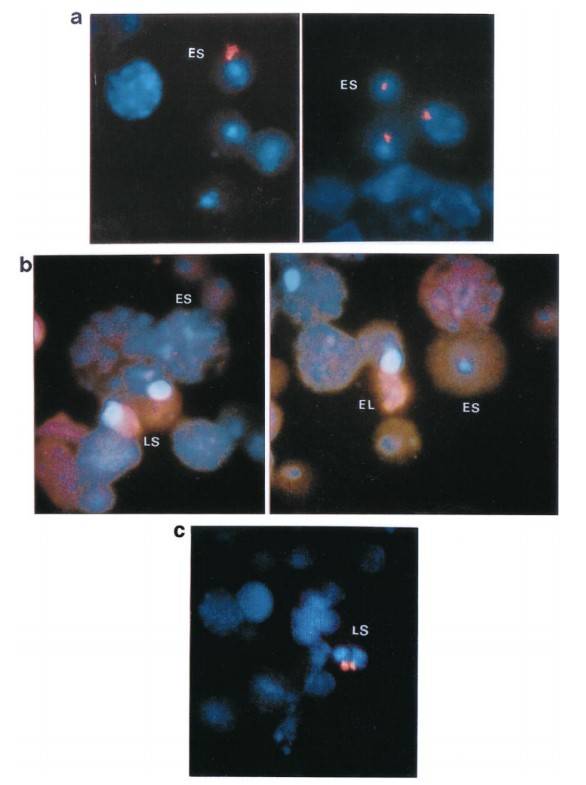

Temporal expression studies indicate that Spam1 is haploidy expressed, with RNA and protein appearing at day 21.5. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry reveal compartmentalization of Spam1 mRNA and protein, suggesting that these transcripts are not shared between spermatids. This lack of sharing results in the production of functionally distinct sperm in males with different Spam1 alleles. Biochemical differences in sperm from these heterozygous males were confirmed by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. Collectively, the results indicate that the Spam1 antigen is not shared among spermatids, potentially providing an explanation for TRD.

To better understand the intracellular distribution of Spam1 RNA in the cytoplasm, RNA-FISH studies were performed on testicular cells carefully isolated from the seminiferous tubules. The results showed that Spam1 transcripts were highly compartmentalized within the cytoplasm of both early and late spermatids (Fig. 6a). In contrast, using Prm1 as a control, the researchers found that its RNA, which is known to be shared across intercellular cytoplasmic bridges, was widely distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 6b). In addition, an experiment using testicular cells from Rb (6.15)/+ males confirmed the compartmentalization of Spam1 RNA in spermatids. In these cells, they observed marked variations in the amount of RNA present between cells at the same developmental stage, as shown in Figure 6c for acrosome-phase spermatids (stages 8-12).

Fig. 6: Distribution patterns of Spam1 and Prm1 mRNA (red staining) in the cytoplasm of early (ES), late (LS), and elongating (EL) spermatids using RNA-FISH. a) Compartmentalization of Spam1 mRNA in the cytoplasm of early spermatids. The red staining is highly clustered. b) Prm1 mRNA shows a diffuse distribution pattern with signal throughout the cytoplasm and is less concentrated in both early and late spermatids. Nuclei of spermatids and other spermatogenic cells are stained blue with DAPI. c) Variation in the quantity of Spam1 mRNA in late spermatids (LS) of the same developmental age from Rb (6.15)/+ male as seen by RNA-FISH. The signal on the right is smaller. Original magnification X1000.

Fig. 6: Distribution patterns of Spam1 and Prm1 mRNA (red staining) in the cytoplasm of early (ES), late (LS), and elongating (EL) spermatids using RNA-FISH. a) Compartmentalization of Spam1 mRNA in the cytoplasm of early spermatids. The red staining is highly clustered. b) Prm1 mRNA shows a diffuse distribution pattern with signal throughout the cytoplasm and is less concentrated in both early and late spermatids. Nuclei of spermatids and other spermatogenic cells are stained blue with DAPI. c) Variation in the quantity of Spam1 mRNA in late spermatids (LS) of the same developmental age from Rb (6.15)/+ male as seen by RNA-FISH. The signal on the right is smaller. Original magnification X1000.Case 2: Okutman, Ö.; et al. Homozygous splice site mutation in ZP1 causes familial oocyte maturation defect. Genes. 2020, 11(4), 382.

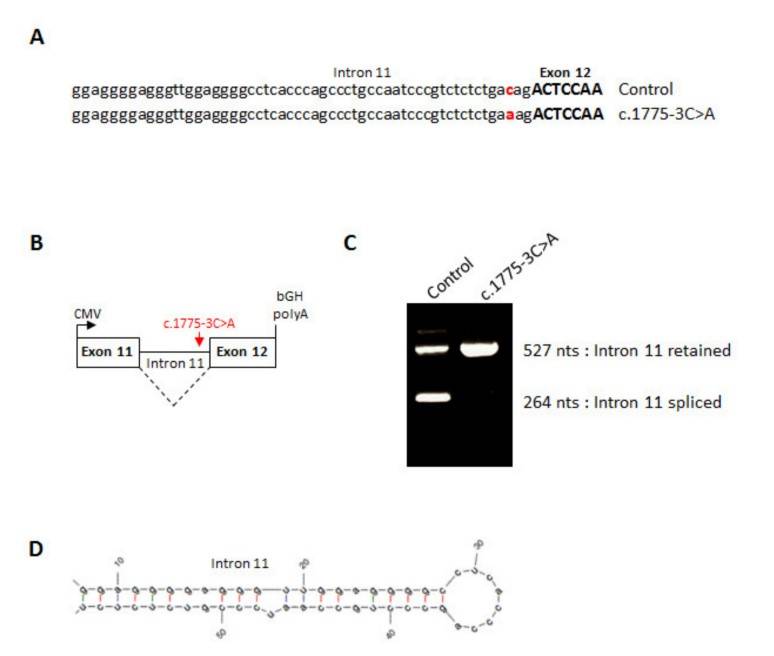

In vitro fertilization (IVF) relies on controlled ovarian hyperstimulation to produce multiple oocytes, with the success of the procedure largely dependent on the availability of mature oocytes. Typically, 70% to 80% of retrieved oocytes are mature, but in rare cases, all may be immature, meaning they have not reached the metaphase II (MII) stage. This complete absence of mature oocytes, despite effective ovarian stimulation over multiple cycles, is a rare cause of primary female infertility for which the genetic factors are largely unknown. This study examines a consanguineous Turkish family with three sisters with recurrent oocyte maturation defects. Whole exome sequencing identified a homozygous splice site mutation (c.1775-3C>A) in the zona pellucida glycoprotein 1 (ZP1) gene. Minigene experiments showed that this mutation leads to the retention of intron 11 between exon 11 and exon 12, resulting in a frameshift and the potential production of a truncated protein.

Fig. 7: Splicing effect of the ZP1 mutation. (A) Sequence of human ZP1 from the end of intron 11 up to the start of exon 12 from a control minigene or a c.1775-3C>A minigene. (B) Line drawing of ZP1 minigene cloned into pcDNA3.1. (C) RT-PCR of wild type or mutant ZP1 mRNA expressed in CHO cells. (D) RNA hairpin structure formed by the end of ZP1 intron 11.

Fig. 7: Splicing effect of the ZP1 mutation. (A) Sequence of human ZP1 from the end of intron 11 up to the start of exon 12 from a control minigene or a c.1775-3C>A minigene. (B) Line drawing of ZP1 minigene cloned into pcDNA3.1. (C) RT-PCR of wild type or mutant ZP1 mRNA expressed in CHO cells. (D) RNA hairpin structure formed by the end of ZP1 intron 11.References

- Martinhago, C. D., & Furtado, C. L. M. (2022). Chapter 5 - Genetics and epigenetics of healthy gametes, conception, and pregnancy establishment: Embryo, mtDNA, and disease. In D. Vaamonde, A. C. Hackney, & J. M. Garcia-Manso (Eds.), Fertility, Pregnancy, and Wellness (pp. 73–89). Elsevier.

- Okutman, Ö., Demirel, C., Tülek, F., Pfister, V., Büyük, U., Muller, J., Charlet-Berguerand, N., & Viville, S. (2020). Homozygous splice site mutation in zp1 causes familial oocyte maturation defect. Genes, 11(4), 382.

- Sugita, H., Takarabe, S., Kageyama, A., Kawata, Y., & Ito, J. (2024). Molecular mechanism of oocyte activation in mammals: Past, present, and future directions. Biomolecules, 14(3), 359.

- Vickram, S., Rohini, K., Srinivasan, S., Nancy Veenakumari, D., Archana, K., Anbarasu, K., Jeyanthi, P., Thanigaivel, S., Gulothungan, G., Rajendiran, N., & Srikumar, P. S. (2021). Role of zinc (Zn) in human reproduction: A journey from initial spermatogenesis to childbirth. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(4), 2188.

- Zheng, Y., Deng, X., & Martin-DeLeon, P. A. (2001). Lack of sharing of spam1 (Ph-20) among mouse spermatids and transmission ratio distortion1. Biology of Reproduction, 64(6), 1730–1738.