Uncategorized Thursday, 2023/03/30

In a new study, researchers from St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital and Rockefeller University in the United States combined their expertise to gain a better understanding of a protein called cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). Mutations in CFTR cause cystic fibrosis, a fatal disease that cannot be cured. The relevant research results were published online in the journal Nature, with the title “CFTR function, physiology and pharmacology at single molecule resolution”.

Currently, treatment with a drug called a potentiator can enhance the CFTR function of some patients; however, it is not clear how potentiator work. This new discovery reveals the mechanism of the function of CFTR and how the pathogenic mutations and potentiator of CFTR affect these functions. With this information, scientists may be able to design more effective treatments for cystic fibrosis.

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disease that causes people to produce excessively sticky mucus. This can clog the respiratory tract and cause lung damage, as well as cause digestive problems. In the United States, the disease affects approximately 35000 people. CFTR is an anion channel that maintains the correct balance of salt and liquid on the epithelium and other membranes. Mutations in CFTR are the cause of cystic fibrosis, but these mutations can affect the function of CFTR in different ways. Therefore, some drugs used to treat this disease can only partially restore the function of specific mutant forms of CFTR.

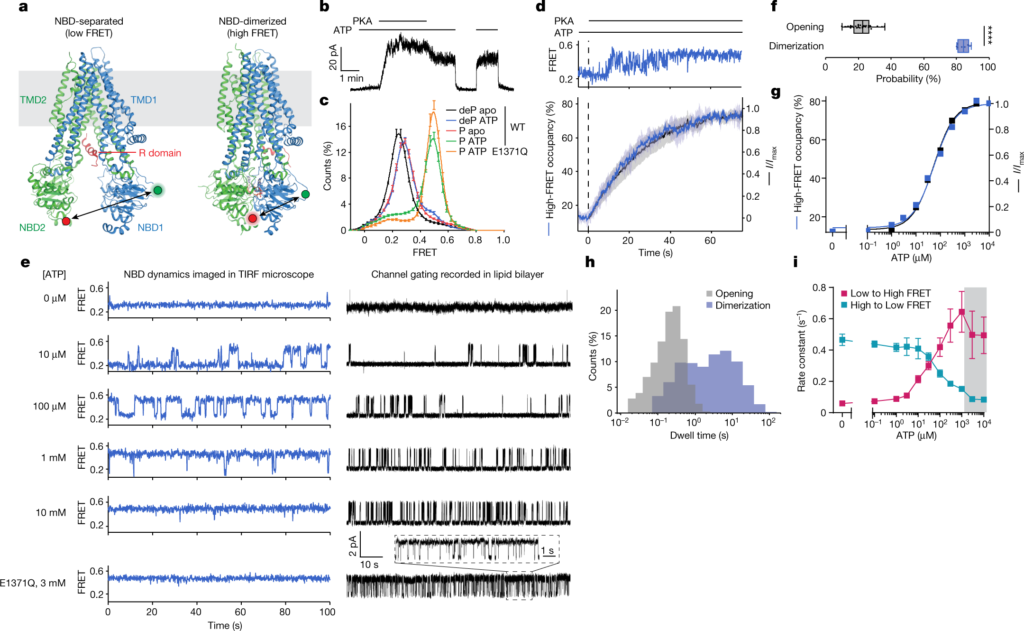

The CFTR structure previously captured in the laboratory of Dr. Jue Chen and colleagues at Rockefeller University shows two different conformations (shapes). These static structural images enable people to see the state of this ion channel when it is open or closed, but the transition between its different states is not fully understood.

Therefore, it is important to infer that the conformational changes of CFTR are important for opening and closing this ion channel, which is also the reason for the electrophysiological characteristics of CFTR that have been analyzed for decades. These findings have sparked interest in visualizing the structural transformation of CFTRs directly and in real-time, and in investigating how conformational changes are affected by pathogenic mutations and drugs used to enhance the function of CFTRs in patients.

Dr. Scott Blanchard, the coauthor of the paper and department of structural biology at St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital, said, “Through this collaboration, we have the opportunity to truly understand the relationship between structure and function. Our laboratory's previous research work on ribosomes and G-protein coupled receptors have shown that this is possible, but few single proteins are more relevant to the treatment of diseases than CFTR, as the treatment of cystic fibrosis aims to improve the defects of this form of protein mutation. Being able to conduct biophysical measurements and obtain quantitative insights of these types is one of the advances in single-molecule imaging, which has never stopped surprising me."

Breakthroughs brought by cooperation The complementary expertise of different research teams is key to these authors' findings. Through electrophysiological and structural research, the research team from Rockefeller University (hereinafter referred to as the Rockefeller team) can guide the research team from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (hereinafter referred to as the St. Jude team) to place single molecular probes. By using single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET), the St. Jude team was able to provide new insights into the mobile components of CFTR.

By integrating cryo-electron microscopy, electrophysiology, and smFRET, the St. Jude team was able to come up with the connections needed to better understand how CFTR works.

“By understanding the structure and behavior of CFTR, we have the potential to help patients with cystic fibrosis,” said Jesper Levring of Rockefeller University, the first author of the paper. “Using these methods - single channel electrophysiology and smFRET - to observe these molecules one at a time, we can associate the function and conformational changes of this ion channel, and associate it with basic structural biology.”

These authors found that CFTR exhibits a hierarchical gating mechanism. The two nucleotide-binding domains of CFTR undergo dimerization before the ion channel is opened. The morphological changes in this dimerized ion channel are related to ATP hydrolysis, a reaction that releases energy, and are used to regulate chloride ion conduction.

The importance of this mechanism insight was further revealed by the discovery that the potentiator drugs, Ivacaftor and GLPG1837, enhance the activity of the ion channel by increasing pore opening during dimerization of the two nucleotide-binding domains of CFTR. Mutations in CFTR that cause cystic fibrosis can reduce the efficiency of this dimerization. These insights will help provide information for finding more effective clinical treatments.

Chen said, “The most satisfying aspect of this new study is that we have answered a question about how CFTR works, which has been a controversial topic in this field for many years. Each individual method has limitations, so you can have good data, but there is still no answer. By combining multiple methods, we have obtained a unified mechanism that allows us to gain an in-depth understanding of how this molecule works.” “With this understanding, we can test how mutations or drugs affect function, which ultimately is our way to obtain better treatments.”

Related Product

CFTR Protein GPCRs

Reference Jesper Levring et al. CFTR function, pathology and pharmacology at single-molecule resolution. Nature, 2023, doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05854-7.